Sequences as Conventional Interfaces

In working with compound data, we've stressed how data abstraction permits us to design programs without becoming enmeshed in the details of data representations, and how abstraction preserves for us the flexibility to experiment with alternative representations. In this section, we introduce another powerful design principle for working with data structures -- the use of conventional interfaces.

In the section Formulating Abstractions with Higher-Order Functions we saw how program abstractions, implemented as higher-order functions, can capture common patterns in programs that deal with numerical data. Our ability to formulate analogous operations for working with compound data depends crucially on the style in which we manipulate our data structures. Consider, for example, the following function, analogous to the count-leaves/2 function of the section Hierarchical Structures, which takes a tree as argument and computes the sum of the squares of the leaves that are odd:

(defun odd? (n)

(=:= 1 (rem (trunc n) 2)))

(defun sum-odd-squares

(('())

0)

(((cons head tail))

(+ (sum-odd-squares head)

(sum-odd-squares tail)))

((elem)

(if (funcall #'odd?/1 elem)

(square elem)

0)))

On the surface, this function is very different from the following one, which constructs a list of all the even Fibonacci numbers , where is less than or equal to a given integer :

(defun even-fibs (n)

(fletrec ((next (k)

(if (> k n)

'()

(let ((f (fib k)))

(if (even? f)

(cons f (next (+ k 1)))

(next (+ k 1)))))))

(next 0)))

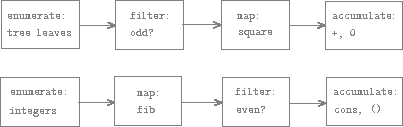

Despite the fact that these two functions are structurally very different, a more abstract description of the two computations reveals a great deal of similarity. The first program

- enumerates the leaves of a tree;

- filters them, selecting the odd ones;

- squares each of the selected ones; and

- accumulates the results using

+, starting with 0.

The second program

- enumerates the integers from 0 to ;

- computes the Fibonacci number for each integer;

- filters them, selecting the even ones; and

- accumulates the results using

cons, starting with the empty list.

A signal-processing engineer would find it natural to conceptualize these processes in terms of signals flowing through a cascade of stages, each of which implements part of the program plan, as shown in figure 2.7. In sum-odd-squares/1, we begin with an enumerator, which generates a "signal" consisting of the leaves of a given tree. This signal is passed through a filter, which eliminates all but the odd elements. The resulting signal is in turn passed through a map, which is a "transducer" that applies the square function to each element. The output of the map is then fed to an accumulator, which combines the elements using +, starting from an initial 0. The plan for even-fibs/1 is analogous.

Figure 2.7: The signal-flow plans for the functions sum-odd-squares/1 (top) and even-fibs/1 (bottom) reveal the commonality between the two programs.

Unfortunately, the two function definitions above fail to exhibit this

signal-flow structure. For instance, if we examine the sum-odd-squares/1

function, we find that the enumeration is implemented partly by the pattern

matching tests and partly by the tree-recursive structure of the function.

Similarly, the accumulation is found partly in the tests and partly in the

addition used in the recursion. In general, there are no distinct parts of

either function that correspond to the elements in the signal-flow description.

Our two functions decompose the computations in a different way, spreading the

enumeration over the program and mingling it with the map, the filter, and the

accumulation. If we could organize our programs to make the signal-flow

structure manifest in the functions we write, this would increase the conceptual clarity of the resulting code.