Functions as Black-Box Abstractions

sqrt/1 is our first example of a program defined by a set of mutually

defined functions. Notice that the definition of sqrt/2 is recursive; that

is, the function is defined in terms of itself. The idea of being able to

define a function in terms of itself may be disturbing; it may seem unclear how

such a "circular" definition could make sense at all, much less specify a

well-defined process to be carried out by a computer. This will be addressed

more carefully in the section Functions and the Processes They Generate.

But first let's consider some other important points illustrated by the

examples of the square-root program.

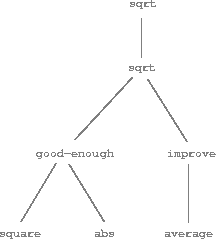

Observe that the problem of computing square roots breaks up naturally into a number of subproblems: how to tell whether a guess is good enough, how to improve a guess, and so on. Each of these tasks is accomplished by a separate function. The entire square-root program can be viewed as a cluster of functions (shown in figure 1.2) that mirrors the decomposition of the problem into subproblems.

Figure 1.2: Procedural decomposition of the square-root program.

The importance of this decomposition strategy is not simply that one is

dividing the program into parts. After all, we could take any large program and

divide it into parts -- the first ten lines, the next ten lines, the next ten

lines, and so on. Rather, it is crucial that each function accomplishes an

identifiable task that can be used as a module in defining other functions. For

example, when we define the good-enough?/2 function in terms of

square/1, we are able to regard the square/1 function as a "black box."

We are not at that moment concerned with how the function computes its result,

only with the fact that it computes the square. The details of how the square

is computed can be suppressed, to be considered at a later time. Indeed, as far

as the good-enough?/2 function is concerned, square/1 is not quite a

function but rather an abstraction of a function, a so-called procedural

abstraction. At this level of abstraction, any function that computes the

square is equally good.

Thus, considering only the values they return, the following two functions for squaring a number should be indistinguishable. Each takes a numerical argument and produces the square of that number as the value.1

(defun square (x) (* x x))

(defun square (x)

(exp (double (log x))))

(defun double (x) (+ x x))

So a function definition should be able to suppress detail. The users of the function may not have written the function themselves, but may have obtained it from another programmer as a black box. A user should not need to know how the function is implemented in order to use it.

Local names

One detail of a function's implementation that should not matter to the user of the function is the implementer's choice of names for the function's formal parameters. Thus, the following functions should not be distinguishable:

(defun square (x) (* x x))

(defun square (y) (* y y))

This principle -- that the meaning of a function should be independent of the parameter names used by its author -- seems on the surface to be self-evident, but its consequences are profound. The simplest consequence is that the parameter names of a function must be local to the body of the function. For example, we used square/1 in the definition of good-enough?/2 in our square-root function:

(defun good-enough? (guess x)

(< (abs (- (square guess) x)) 0.001))

The intention of the author of good-enough?/2 is to determine if the square of the first argument is within a given tolerance of the second argument. We see that the author of good-enough?/2 used the name guess to refer to the first argument and x to refer to the second argument. The argument of square/1 is guess. If the author of square/1 used x (as above) to refer to that argument, we see that the x in good-enough?/2 must be a different x than the one in square. Running the function square must not affect the value of x that is used by good-enough?/2, because that value of x may be needed by good-enough?/2 after square/1 is done computing.

If the parameters were not local to the bodies of their respective functions, then the parameter x in square/1 could be confused with the parameter x in good-enough?/2, and the behavior of good-enough?/2 would depend upon which version of square/1 we used. Thus, square/1 would not be the black box we desired.

A formal parameter of a function has a very special role in the function definition, in that it doesn't matter what name the formal parameter has. Such a name is called a bound variable, and we say that the function definition binds its formal parameters. The meaning of a function definition is unchanged if a bound variable is consistently renamed throughout the definition.2 If a variable is not bound, we say that it is free. The set of expressions for which a binding defines a name is called the scope of that name. In a function definition, the bound variables declared as the formal parameters of the function have the body of the function as their scope.

In the definition of good-enough?/2 above, guess and x are bound variables but <, -, abs, and square/1 are free. The meaning of good-enough?/2 should be independent of the names we choose for guess and x so long as they are distinct and different from <, -, abs, and square. (If we were running this code in the LFE REPL and renamed guess to a variable that had been set earlier in the session, we would have introduced a bug by capturing that previously set variable. It would have changed from free to bound.) The meaning of good-enough?/2 is not independent of the names of its free variables, however. It surely depends upon the fact (external to this definition) that the symbol abs names a function for computing the absolute value of a number. good-enough?/2 will compute a different function if we substitute cos for abs in its definition.

Internal definitions and block structure

We have one kind of name isolation available to us so far: The formal parameters of a function are local to the body of the function. The square-root program illustrates another way in which we would like to control the use of names. The existing program consists of separate functions:

(defun sqrt (x)

(sqrt (* 0.5 x) x))

(defun sqrt (guess x)

(if (good-enough? guess x)

guess

(sqrt (improve guess x)

x)))

(defun good-enough? (guess x)

(< (abs (- (square guess) x)) 0.001))

(defun improve (guess x)

(average guess (/ x guess)))

(defun average (x y)

(/ (+ x y) 2))

(defun abs

((x) (when (< x 0)) (- x))

((x) x))

(defun square (x) (* x x))

The last three are fairly general, useful in many contexts. This leaves us with the following special-purpose functions from our square-root program:

(defun sqrt (x)

(sqrt (* 0.5 x) x))

(defun sqrt (guess x)

(if (good-enough? guess x)

guess

(sqrt (improve guess x)

x)))

(defun good-enough? (guess x)

(< (abs (- (square guess) x)) 0.001))

(defun improve (guess x)

(average guess (/ x guess)))

The problem with this program is that the only function that is important to users of the square-root program is sqrt/1. The other functions (sqrt/2, good-enough?/2, and improve/2) only clutter up their minds. They may not define any other function called good-enough?/2 as part of another program to work together with the square-root program, because the square-root program needs it. The problem is especially severe in the construction of large systems by many separate programmers. For example, in the construction of a large library of numerical functions, many numerical functions are computed as successive approximations and thus might have functions named good-enough?/2 and improve/2 as auxiliary functions. We would like to localize the subfunctions, hiding them inside sqrt/1 so that the square-root program could coexist with other successive approximations, each having its own private good-enough?/2 function. To make this possible, we allow a function to have internal definitions that are local to that function. For example, in the square-root problem we can write

(defun sqrt (x)

(fletrec ((improve (guess x)

;; Improve a given guess for the square root.

(average guess (/ x guess)))

(good-enough? (guess x)

;; A predicate which determines if a guess is

;; close enough to a correct result.

(< (abs (- (square guess) x)) 0.001))

(sqrt (guess x)

;; A recursive function for approximating

;; the square root of a given number.

(if (good-enough? guess x)

guess

(sqrt (improve guess x)

x))))

;; the main body of the function

(sqrt (* 0.5 x) x)))

The use of flet ("function let"), flet* (sequential "function let"s) , and fletrec ("recursive function let"s) allows one to define locally scoped functions, or functions that are only scoped within the given form. This is one of the classic solutions to the problem of naming collisions in older Lisp programs.3

But there is a better idea lurking here. In addition to internalizing the definitions of the auxiliary functions, we can simplify them. Since x is bound in the definition of sqrt/1, the functions good-enough?/2, improve/2, and sqrt/2, which are defined internally to sqrt, are in the scope of x. Thus, it is not necessary to pass x explicitly to each of these functions. Instead, we allow x to be a free variable in the internal definitions, as shown below. Then x gets its value from the argument with which the enclosing function sqrt/1 is called. This discipline is called lexical scoping.4

(defun sqrt (x)

(fletrec ((improve (guess)

;; Improve a given guess for the square root.

(average guess (/ x guess)))

(good-enough? (guess)

;; A predicate which determines if a guess is

;; close enough to a correct result.

(< (abs (- (square guess) x)) 0.001))

(sqrt-rec (guess)

;; A recursive function for approximating

;; the square root of a given number.

(if (good-enough? guess)

guess

(sqrt-rec (improve guess)))))

;; the main body of the function

(sqrt-rec (* 0.5 x))))

Note that this required the renaming of the sqrt/2 function. We dropped the

arity of sqrt/2 from 2 to 1, thus causing a name collision with our

outer-most sqrt/1 and thus renamed it to sqrt-rec/1.

The idea of this sort of nested structure originated with the programming language Algol 60. It appears in most advanced programming languages and, as mentioned, used to be an important tool for helping to organize the construction of large programs.

Modules, exports, and private functions

While Algol 60 pioneered the concept of nested function definitions,5 later versions of Algol 68 advanced the concept of modules.6 This made a significant impact in the world of practical computing to the extent that most modern languages have some form of module support built in.

LFE supports modules. The proper way to provide a "black box" program to an LFE developer for their use is to define all the functions in one or more modules and export only those functions which are intended to be consumed by a developer.

Instead of using fletrec, here is the square-root program using a module

with one exported function:

(defmodule sqrt

(export (sqrt 1)))

(defun sqrt (x)

(sqrt (* 0.5 x) x))

(defun sqrt (guess x)

(if (good-enough? guess x)

guess

(sqrt (improve guess x)

x)))

(defun good-enough? (guess x)

(< (abs (- (square guess) x)) 0.001))

(defun improve (guess x)

(average guess (/ x guess)))

(defun average (x y)

(/ (+ x y) 2))

(defun abs

((x) (when (< x 0)) (- x))

((x) x))

(defun square (x) (* x x))

Then from the LFE REPL we can compile the module and run it, using the LFE (module:function ...) calling syntax

> (c "ch1/sqrt.lfe")

#(module sqrt)

> (sqrt:sqrt 25)

5.000012953048684

> (sqrt:sqrt 1)

1.0003048780487804

> (sqrt:sqrt 2)

1.4142156862745097

Attempting to use functions that are not exported results in an error

> (sqrt:sqrt 1 25)

exception error: undef

in (: sqrt sqrt 1 25)

We will use modules extensively to help us break up large programs into tractable pieces.

1. It is not even clear which of these functions is a more efficient implementation. This depends upon the hardware available. There are machines for which the "obvious" implementation is the less efficient one. Consider a machine that has extensive tables of logarithms and antilogarithms stored in a very efficient manner. ↩

2. The concept of consistent renaming is actually subtle and difficult to define formally. Famous logicians have made embarrassing errors here. ↩

3. This is one of the pillars of the structured programming paradigm. ↩

4. Lexical scoping dictates that free variables in a function are taken to refer to bindings made by enclosing function definitions; that is, they are looked up in the environment in which the function was defined. We will see how this works in detail in chapter 11 when we study environments and the detailed behavior of the interpreter. ↩

5. Also called block structures. ↩

6. Extensions for module support in Algol 68 were released in 1970. In 1975, Modula was the first language designed from the beginning to have support for modules. Due to Modula's use of the "dot".to separate modules and objects, that usage became popular in such languages as Python and and Java. In contrast, Erlang and LFE use the colon:to separate modules from functions. ↩