Casting SPELs in Lisp Flavoured Erlang

A Bold New LFE Take on the Common Lisp Comic Classic

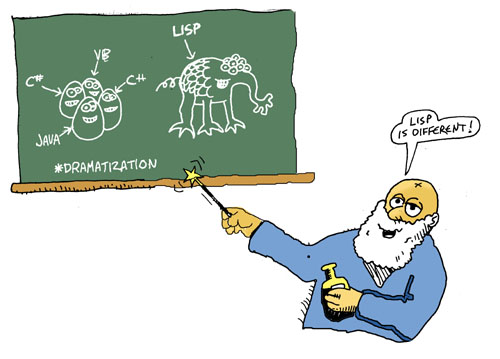

Anyone who has ever learned to program in Lisp will tell you it is very different from any other programming language. It is different in lots of surprising ways -- this comic book will let you find out how Lisp's unique design makes it so powerful!

This tutorial has small bits of Lisp code that are presented as it looks when using the LFE REPL (the "interactive interpreter"). The LFE prompt looks like this:

>

Code entered in the REPL looks like this:

> (+ 1 1)

2

Results will come right afterwards, in their own text block, just like you saw in that example just now.

When you copy the code from this book into your own LFE REPL, be sure

not to copy the > prompt! Just copy the code :-)

What will you be copying, you ask? A-ha! This is the best part: your own text adventure game!

First, though, we're going to have to cover some basics. But take heart: you'll be coding up some gamey goodness in no time ;-)

What is LFE?

LFE stands for "Lisp Flavoured Erlang". It's a Lisp dialect written on top of the Erlang Virtual Machine (also known as the "BEAM"). Erlang syntax looks like this:

factors(N) ->

factors(N,2,[]).

factors(1,_,Acc) -> Acc;

factors(N,K,Acc) when N rem K == 0 ->

factors(N div K,K, [K|Acc]);

factors(N,K,Acc) ->

factors(N,K+1,Acc).

LFE syntax looks like this:

(defun factors (n)

(factors n 2 '()))

(defun factors

((1 _ acc)

acc)

((n k acc) (when (== 0 (rem n k)))

(factors (div n k) k (cons k acc)))

((n k acc)

(factors n (+ k 1) acc)))

You don't need to worry about that code or what it means: it's just there to give you a "feel" of these two Erlang syntaxes (LFE in particular!), a visual sense of how the two languages are the same underneath, but superficially different (we'll be discussing syntax very shortly!)

If you don't have LFE installed on your computer, no need to worry -- in the first chapter, you will be setting up LFE so that you can follow along in this book.

Casting SPELs in LFE?

The decision to port Casting SPELs in Lisp to LFE was based on two things. Firstly, it was inspired by an interest in providing the community and new comers with a greater number of interesting learning tools for the language. Secondly, whimsy. The original for Common Lisp was such great fun; how delightful to share that with the LFE community?

It's actually very easy to port basic Common Lisp to LFE. But once you get deeper than syntax, things can diverge quite strongly. It turns out that the immutable data of Erlang and LFE made porting this comic book quite tricky. In the end, I had to give up all hope of the whimsy, and switch gears to basic application architecture best practices.

As such, you will see a very different comic in this book than in the others: immutable data, Erlang records for tracking game state, state being returned by most functions, and many more. At first I was disappointed: this wasn't going to be the best casual, entry-level introduction to LFE.

Upon further reflection, however, I came to embrace this difference. Erlang, and thus LFE, is not just another language you can pick up in a weekend and hack on for fun. It's not a Python, or Ruby, or Julia. Erlang wasn't created to solve the human problem of making a better high-level language, of making programming fit in the brains of new developers more easily. Rather, Erlang was created to hammer a very different nail, and quite the sledgehammer it turned out to be: pounding out some impressive fault-tolerant, distributed systems. Erlang was created to so that programmers could make better industrial grade telecommunications infrastructure.

That's not a Sunday afternoon hacking project.

And this brings me to the point: LFE is not a casual Lisp. It's a Lisp for those who want to build distributed applications like the Erlang software that powers 40% of the world's telecommunications. As a systems programming language, it's somewhat more involved and has many more moving parts than the sort of languages that are picked up like hobbies or to crunch data at work. It's a complete programming language, but it's also like an operating system; a highly-concurrent distributed operating system. If you've never programmed before, I would highly recommend learning another language first, waiting to tackle the concepts behind distributed systems once you have a strong foundation in place.

So why build a game with it? Well, games can be fun when played alone -- and often are. But they can be even more fun when played with good friends. Even lots of friends! By learning to write games in an industrial-strength Lisp which specializes in distributed, fault-tolerant, message-passing applications, you're getting a foundation that can help you build the next SPEL-casting MMOMUD :-) But I digress.

As a result of these ponderings, I concluded the following: the concerns about introducing records, pattern matching, guards, immutable data, and process servers paled in comparison to the other potential ways this comic book could have been rendered for use on the Erlang VM (don't worry, there's no OTP!). And for those who are ready to jump into the world of functional programming for distributed systems, this is a super fun way to start, giving you an intuition for some of the basic building blocks you will use in every LFE application you build from here on out.

Enjoy!

About

This Gitbook (available here) is a work in progress, converting Dr. Conrad Barski's original Common Lisp comic book adventure game to Lisp Flavoured Erlang. It was very kind of Dr. Barski to share his work with the Lisp community licensed as GNU Free Documentation, thus allowing others to adopt it for their own preferred language.

Other editions of the book include:

Contributing

If you found a bug, typo, inconsistency, etc., feel free to open a ticket or even submit a pull request!

Building the Book

To build a local copy of the book, install the dependencies:

$ make deps

On Linux, you'll need to run that with sudo.

Then install the gitbook modules:

$ make setup

Finally, build the book:

$ make book