Bertrand Russell

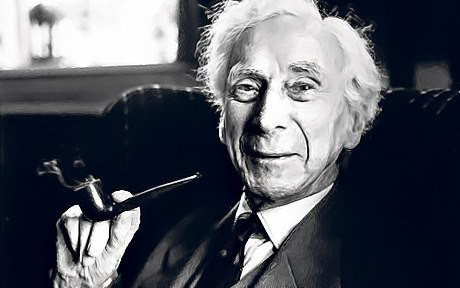

Figure P.2: Bertrand Russell, 1958.

Bertrand Russell was born in 1872 into a family of the British aristocracy. His early life was colored with tragedy: by the time he was six years old, he had lost his mother, sister, father, and grandfather. He was a deeply pensive child naturally inclined towards philosophical topics, and by 1883 -- at the age of 11 -- he was set upon the path for the first half of his life. It was at this time that his brother was tutoring him on Euclid's geometry:

"This was one of the great events of my life, as dazzling as first love. I had not imagined that there was anything so delicious in the world. After I had learned the fifth proposition, my brother told me that it was generally considered difficult, but I had found no difficulty whatever. This was the first time it had dawned upon me that I might have some intelligence. From that moment until Whitehead and I finished Principia ... mathematics was my chief interest, and my chief source of happiness."1

Russell continues in his biography, sharing how this time also provided the initial impetus toward the Principia Mathematica:

"I had been told that Euclid proved things, and was much disappointed that he started with axioms. At first I refused to accept them unless my brother could offer me some reason for doing so, but he said: 'If you don't accept them we cannot go on', and as I wished to go on, I reluctantly admitted them pro tem. The doubt as to the premisses of mathematics which I felt at that moment remained with me, and determined the course of my subsequent work."

In 1900, Russell attended the First International Conference of Philosophy where he had been invited to read a paper. In his autobiography, he describes this fateful event:

"The Congress was a turning point in my intellectual life, because I there met Peano. I already knew him by name and had seen some of his work, but had not taken the trouble to master his notation. In discussions at the Congress I observed that he was more precise than anyone else, and that he invariably got the better of any argument upon which he embarked. As the days went by, I decided that this must be owing to his mathematical logic. I therefore got him to give me all his works, and as soon as the Congress was over I retired to Fernhurst to study quietly every word written by him and his disciples. It became clear to me that his notation afforded an instrument of logical analysis such as I had been seeking for years, and that by studying him I was acquiring a new powerful technique for the work that I had long wanted to do. By the end of August I had become completely familiar with all the work of his school. I spent September in extending his methods to the logic of relations. It seemed to me in retrospect that, through that month, every day was warm and sunny. The Whiteheads stayed with us at Fernhurst, and I explained my new ideas to him. Every evening the discussion ended with some difficulty, and every morning I found that the difficulty of the previous evening had solved itself while I slept. The time was one of intellectual intoxication. My sensations resembled those one has after climbing a mountain in a mist when, on reaching the summit, the mist suddenly clears, and the country becomes visible for forty miles in every direction. For years I had been endeavoring to analyse the fundamental notions of mathematics, such as order and cardinal numbers. Suddenly, in the space of a few weeks, I discovered what appeared to be definitive answers to the problems which had baffled me for years. And in the course of discovering these answers, I was introducing a new mathematical technique, by which regions formerly abandoned to the vaguenesses of philosophers were conquered for the precision of exact formulae. Intellectually, the month of September 1900 was the highest point of my life."2

Russell sent an early edition of the Principia to Peano after working on it for three years. A biographer of Peano noted that he "immediately recognized it's value ... and wrote that the book 'marks an epoch in the field of philosophy of mathematics.'" 3 Over the course of remaining decade, Russell and Whitehead continued to collaborate on the Principia, a work that ultimately inspired Gödel's incompleteness theorems and Church's -calculus.

1. The 1998 reissued hardback "Autobiography" of Bertrand Russell, pages 30 and 31. ↩

2. Ibid., page 147. ↩

3. Kennedy, page 105-106. ↩